Bicycles and Women on Vintage Cycling Posters [From BA 42-500]

"A remarkable connection between women’s bodies and bicycling resulted at the end of the nineteenth century from the felicitous encounter of two technical developments."

Since the invention of the bicycle, men have often attempted to discourage women from riding it or have commented on the ambiguity of the relationship between women’s bodies and the two-wheeled machine. The dominant and often unspoken reason for male discomfort with women’s cycling was/is men’s fear or concern that women would feel sexual arousal from a combination of their sitting position on a bicycle and the cycling motion.

Another reason put forward in medical and popular journals of the time was the concern that cycling would negatively interfere with women’s childbearing abilities. Despite the claim by several doctors that cycling could produce ill effects on female bodies, the medical profession eventually endorsed cycling on the rationale that "women’s role in achieving a superior race type could be enhanced by regular use of the bicycle" and by the claim by some doctors that cycling helped women cure hysteria (Sims 126).

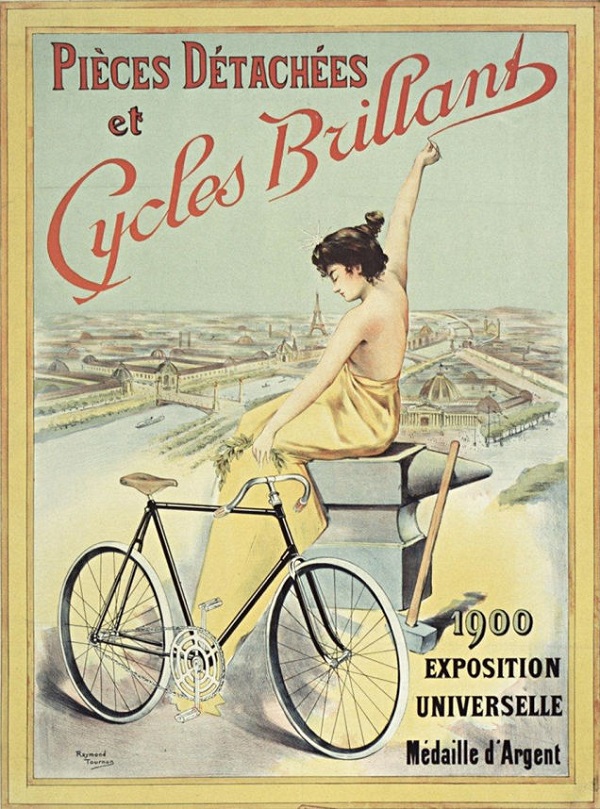

A remarkable connection between women’s bodies and bicycling resulted at the end of the nineteenth century from the felicitous encounter of two technical developments. Color lithography, which enabled the creation of large colorful posters, came into being in the 1870s as the bicycle was undergoing important and definitive mechanical innovations. Both lithographers and bicycle manufacturers were eager to show off their new machines and thus organized innumerable exhibitions and shows that fostered interest and sales. Fierce competition among bicycle companies matched a similarly fierce competition among lithographers. The fusion of these two groups and innovations resulted in remarkable visual creations in colorful posters.

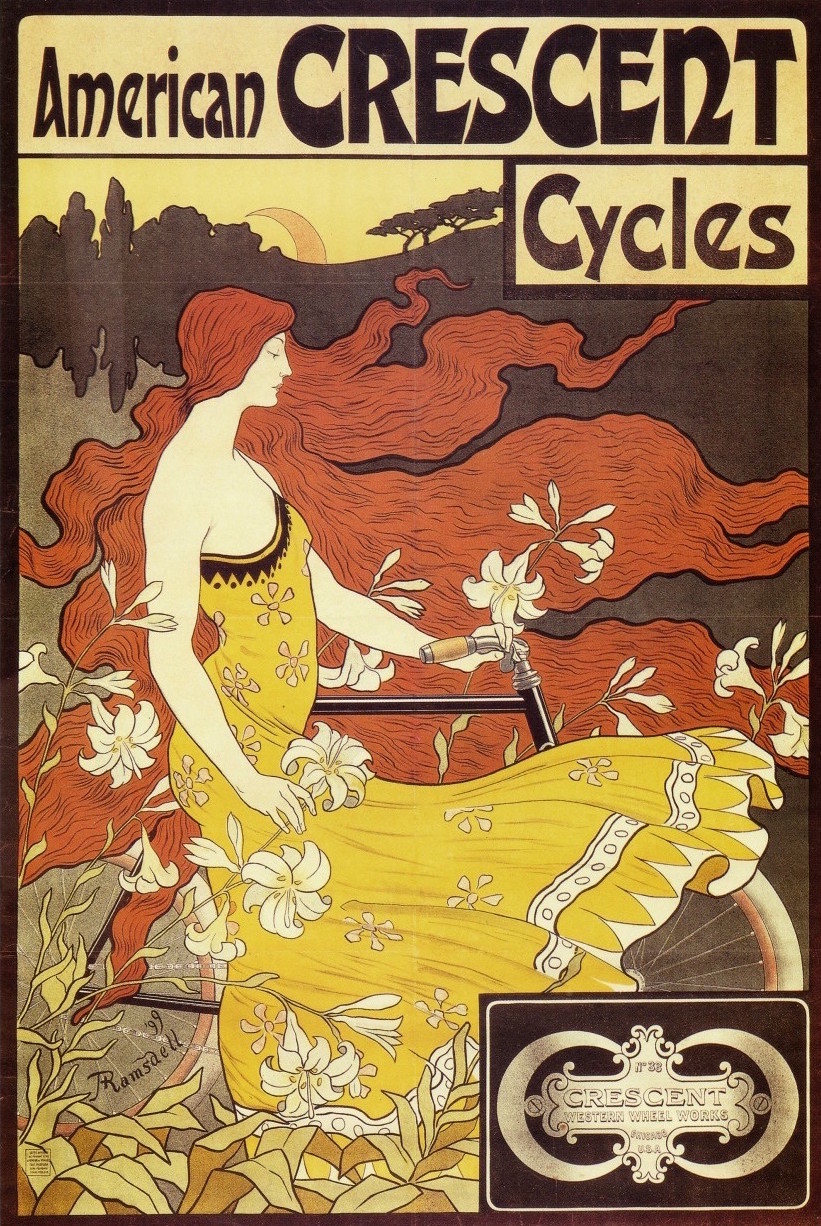

Since large posters were best used as tools for mass marketing, we see a proliferation of them after 1890, when the price of bicycles decreased considerably thanks to mass production of these vehicles in France, Germany, England and the United States. As poster artists came to appreciate the unlimited promise of imagery connected with the bicycle, and bicycle manufacturers realized the advertising potential of posters, an interesting marriage of the two occurred, and “by the turn of the century, more posters were created for bicycles than for any other product” (Rennert 3). An additional common feature of both industries was their multinational composition, so that we have, for instance, Rumanian or Czech artists working for a Parisian printer and producing posters of bicycles manufactured in England or France by a company owned by Americans.

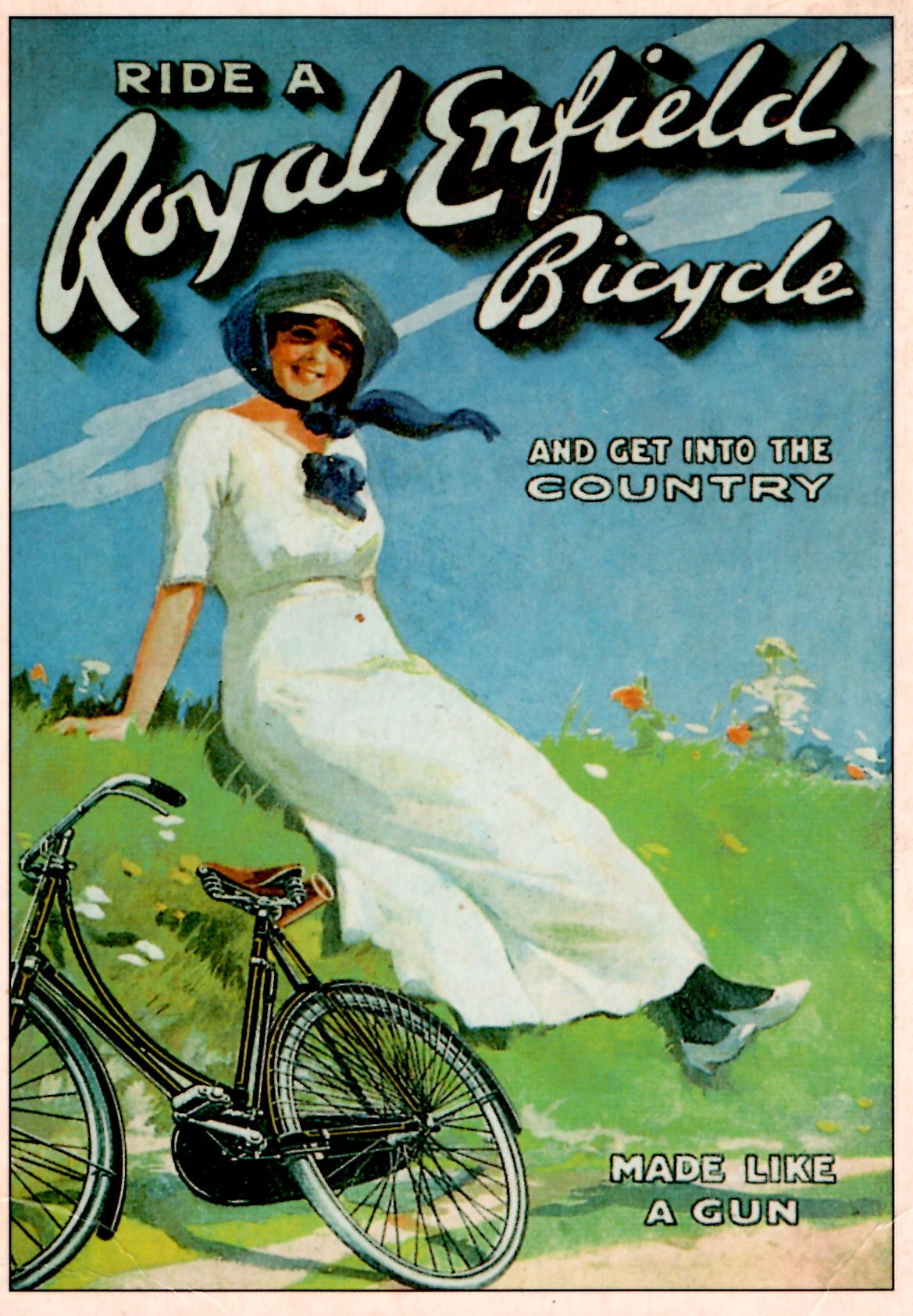

Images of women with bicycles or bicycle parts became the main staple of these posters, as witnessed by Rennert’s collection of one hundred posters produced during this period where about 85% of them depict a woman in contact with a bicycle. Among the reasons for the proliferation of female representations are the explicit suggestions that handling a bicycle is easy, and that women did not lose, but rather enhanced, their charms by riding or interfacing with a bicycle.

One of the criteria for an effective cycling poster was that “it must deliver its message with no uncertain voice, and if possible, without the help of explanatory lettering, or with very little” (Rennert 4). Must we deduce, therefore, that manufacturers of tires, chains or frames expected women to relate immediately with these products and be lured into buying them? Or should we perceive these images as sending a clearer, though subtle message to men, who, supposedly charmed by the women represented, would be lured to acquire the goods publicized? As the aims of advertising have changed very little over the course of centuries, this latter hypothesis may be closer to the truth as the main objective of the sponsors was to sell the products advertised—and men were still the more numerous and richer customers. As with later advertising for automobiles and the obvious and successful marketing association between sexy women and expensive cars, the sexual titillation or innuendos suggested in many of these posters was directed at male buyers, rather than at the female customers of the time.

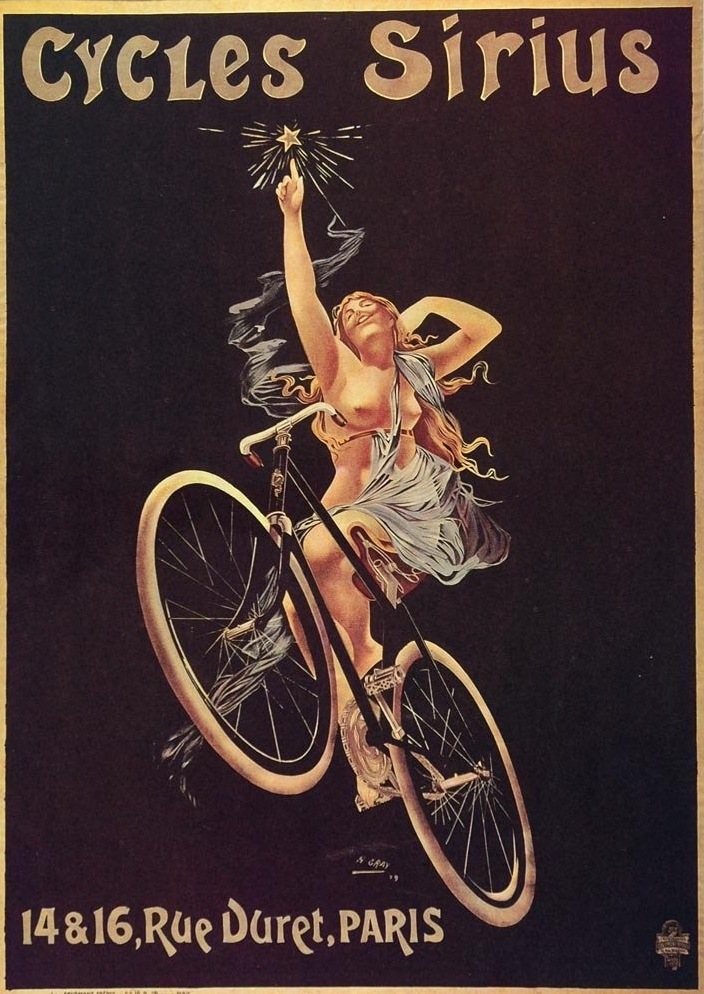

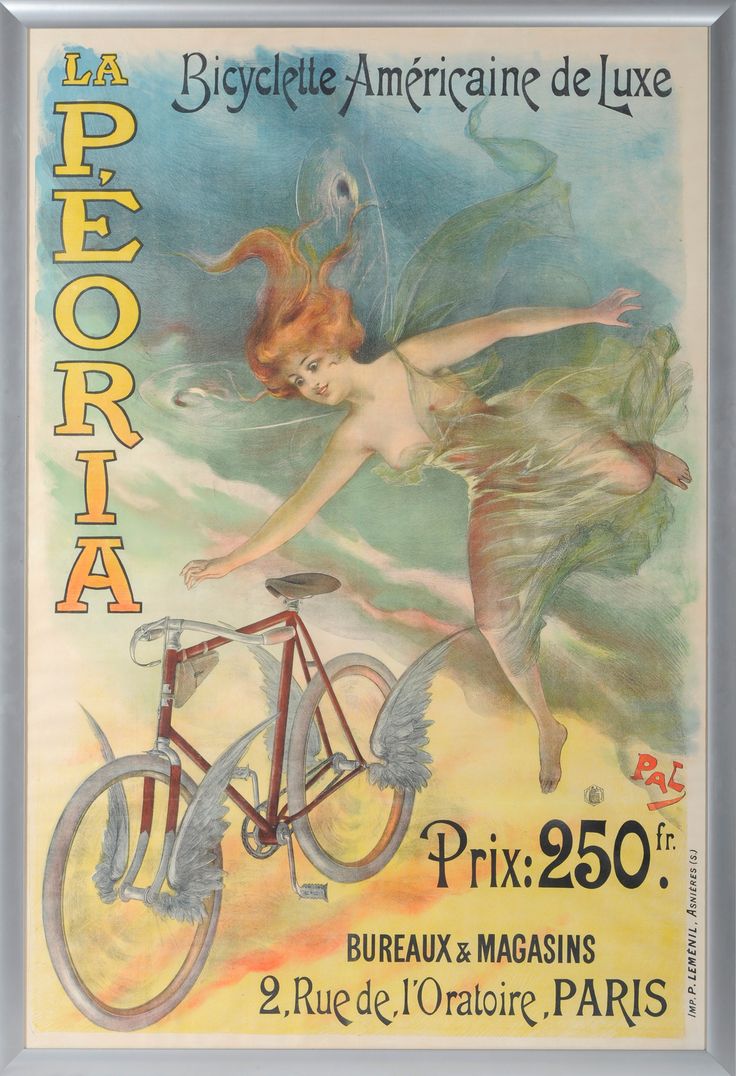

The implicit messages to women in many of these posters, however, are revolutionary for fin-de-siècle society. One suggestion was that it was acceptable for a woman to get out of the domestic walls where she was supposedly relegated by contemporary mores by mounting a bicycle and traveling to unspecified destinations. While many posters present women covered with long-sleeved blouses and ankle-long skirts, as contemporary fashion dictated—while showing at the same time an unrealistic freedom of physical movement possible in these garments—many other images show women scantily dressed or with exposed bare breasts, thighs or buttocks.

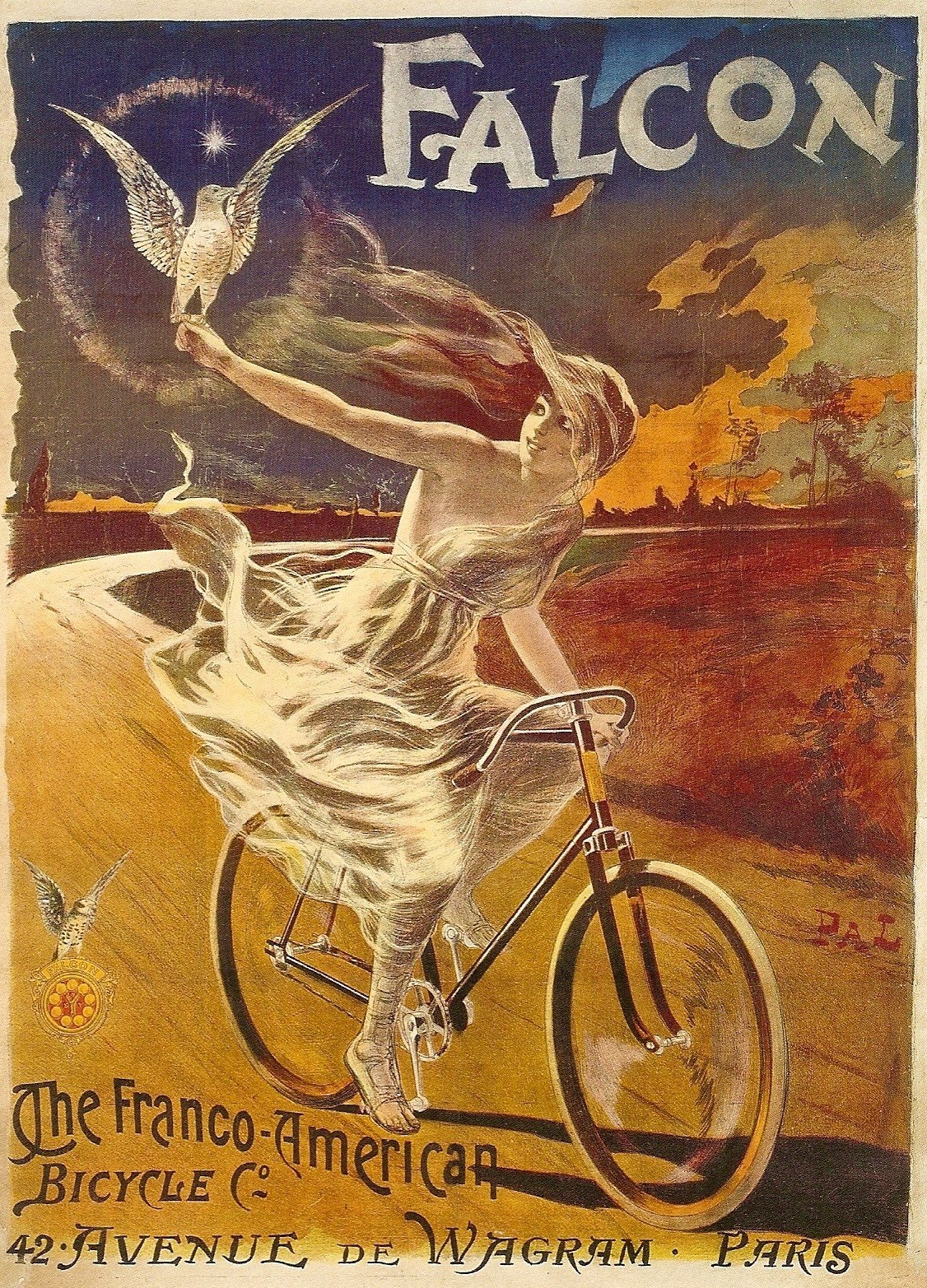

What is perhaps more striking than the naked body parts is the facial expression of most of the women depicted. Some women show sheer ecstasy and full concentration in the free and flowing movement of cycling, as depicted in posters by the well- known Viennese lithographer J. Weiner around 1900 (Rennert 45) or in the work of the artist Pal (pseudonym of Jean de Paléologue, a Rumanian-born artist) produced for Falcon bicycles around 1895 (25).

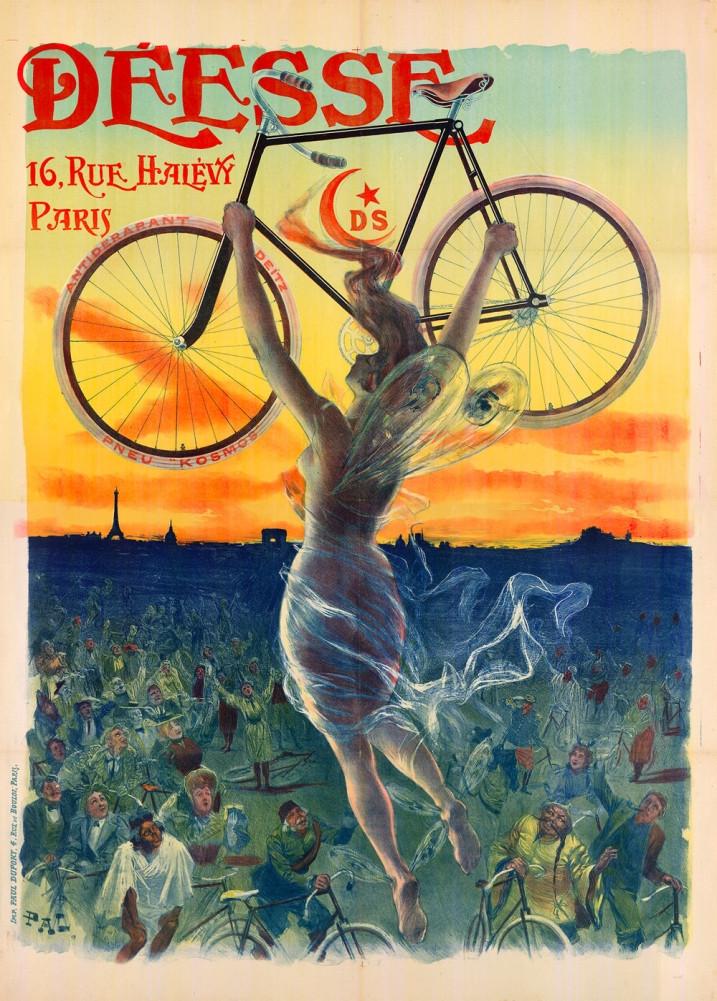

Thanks to their classical training in painting, Pal and other poster artists of the time used extensively mythological or allegorical motifs and figures for which women and their bodies were well suited. One of Pal’s posters shows a scantily dressed woman flying high over a clearly French/Parisian skyline holding tightly a men’s bicycle, while a socially, racially and ethnically diverse crowd looks up with admiration, jubilation and surprise. Befittingly, the cycle advertised in this poster is named Déesse, or Goddess, and the woman well fits the role of a queen-like figure dominating the people of the entire globe (Rennert 62).

The advent of the car gradually but surely trampled the bicycle as a recreational and utilitarian vehicle, as well as a status symbol, since the middle and upper classes saw the new automobile as a tool that would distinguish them from the lower classes. Likewise, women and their bodies became the metaphor of the vehicle, used to encourage the possession of the sleeker, more expensive, and motorized means of transportation. Ever-new advertising instruments replaced the colorful posters, too, and yet over a century later, these posters remain visually stunning testaments to a time in which bicycling was thought of as not only godly, but beautiful and liberating.

SOURCES CITED

Rennert J. (1973) 100 Years of Bicycle Posters (New York, Evanston, San Francisco, London: Harper & Row).

Sims S. (1991) “The Bicycle, the Bloomer and Dress Reform in the 1890s” in P. A. Cunningham and S. Vaso (Eds.) Dress and Popular Culture, pp. 125-145 (Bowling Green, Ohio: Popular Press).